Why picking the wrong retirement date could cost you a lot of money

Part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014 legalized the failure to apply specific mechanisms to prevent pay inversions in the pensions of uniformed services retirees. These pay inversions can cost retirees tens of thousands of dollars in retirement and are based on the formula for determining a retiree’s first Cost of Living Adjustment COLA for inflation.

This information was analyzed in a widely circulated graduate research thesis written by Colonel Douglas J. Fowler as part of his Air War College Air University studies, which is the basis for much of this article.

Specifically, this formula creates a variable system that punishes members who retire in the first month of a fiscal quarter and at certain times during the year, thus creating a COLA Trap.

Current active duty members can avoid the pay inversion in three ways.

- Retire at the end of the last month of a fiscal quarter

- Avoid a September or a 3rd quarter retirement entirely

- A first-quarter retirement is best, and March is optimal

We’ve summarized Colonel Fowler’s thesis and added new information to help clarify how you can avoid falling into this costly mistake.

An example of how costly the COLA Trap can be

If you’re not vigilant in how and when you take retirement, you could be shortchanging you and your family’s retirement income significantly for the rest of your lives.

Consider the following example put forth by Colonel Fowler.

Lt. Colonels Johnny Late and Jane Early joined the United States Air Force on the same day, promoted to the same ranks on the same days, and completed 20 years of active duty service on the same day. Lt. Colonel Late retired one month later than Lt. Colonel Early, but unexpectedly began receiving a pension $1,000 a year less than Lt. Colonel Early upon receipt of their first Cost of Living Adjustment the January after they retired. Despite all being equal except for serving one month longer, Lt. Colonel Late will continue to receive a smaller pension for the rest of his life.

This shortcoming in the system is not uncommon. From 2000 through 2023, it’s estimated that the aggregate of service member pension payments is $272 million less than expected.

Understanding how retirement pay is calculated

Service members can prevent lifelong pay inversion by retiring in a few select months.

The solution lies primarily in fully understanding the High-3 Pension System, also known as the High-36 system. This is because there will continue to be retirees under this system until January 2048, and because so few eligible members opted for the Career Status Bonus/REDUX system.

The first Blended Retirement System members will not retire until January 1, 2026.

Servicemembers who entered active duty after September 8, 1980, have pensions calculated using the average of their highest 36 months of base pay. For most retirees, this is the final 36 months of their pay.

After 20 years of service, a member’s monthly pension is 2.5% of the average of their highest 36 months of base pay for each year they have served. For example, serving exactly 20 years results in 50% of the average of those highest 36 months of base pay.

Each year adds another 2.5% of base pay, so retiring after 24 years would result in 60% of base pay. Or, each added month of service beyond 20 years amounts to about a 0.21% increase in retirement pay.

Unless a servicemember is medically retired, they must retire on the first day of a given month, meaning there are only 12 possible retirement dates in a given year.

In addition to an annual across-the-board percent pay increase in the National Defense Authorization Act, retirees may also receive an across-the-board COLA increase on December 1 each year. The retiree COLA is determined by an automated formula tied to inflation and the Consumer Price Index, not the National Defense Authorization Act.

Your first COLA compares quarters in the same calendar year, which is different from all other COLAs that compare inflation from the same quarters year over year. You will receive your first COLA effective Dec. 1, the same day as everyone else, but because you’ll have been retired for only part of a year, the calculation differs this once. You’ll get a partial COLA increase as a result.

Working longer might lead a servicemember to believe that would add up to more money in retirement, but that doesn’t account for the COLA. In the long term, a better initial COLA can add up to more retirement pay than a few more months of active duty service.

An annual COLA is the difference in inflation between two calendar quarters spaced a year apart.

The COLA formula treats all retirees equally as long as they have been retired for over a year. But that is not the case for retirees who have been retired for less than a year.

Because the active duty annual pay raise is governed by the National Defense Authorization Act and the retiree annual pay raise is an automated formula tied to inflation, retiree pay raises outpace active duty pay raises in some years.

In years with a very low or no active duty pay raise and very high inflation, some retirement-eligible active duty members would have received a higher pension if they had retired a few months earlier. This concept that a retirement-eligible member could have earned a larger pension by retiring earlier is called a pay inversion.

The High-3 System pay inversion and COLA for new High-3 retirees

An audit in 2012 revealed a pay inversion flaw in the High-3 system’s COLA for retirees who had been retired for less than a year.

In 2014, Congress passed the annual National Defense Authorization Act. The Act clarified something known as the Tower Amendment, an existing law that applied to High-3 retirees only on the day they retired, not on the day of their first COLA.

This prevented most retirees from seeking to correct inversions and get retroactive retirement benefits back to the year 2000, when retirees first started receiving annuities under the High-3 formula.

Since the Act became law, current retirees have no recourse, but current active duty members can make choices to prevent future pay inversions.

The formula for determining the first COLA for High-3 retirees is different than the COLA formula for retirees who have been retired for more than a year.

- If you retire in the first quarter, your first COLA will be the average inflation of the third quarter of the year you retire minus the inflation rate of the last quarter of the prior year.

- If you retire in the second quarter, your first COLA will be the average inflation of the third quarter of the year you retire minus the inflation rate of the first quarter of the same year.

- If you retire in the third quarter, your first COLA will be the average inflation of the third quarter of the year you retire minus the inflation rate of the second quarter of the same year.

- If you retire in the fourth quarter, you won’t receive a COLA that year because you’re only a month or two into your retirement date, and the base quarter is subtracted from itself.

For example, under the current system, October 1 retirees are not eligible for a COLA increase for 14 months because COLA increases are based on quarterly inflation statistics. This is a complicated calculation that Colonel Fowler’s thesis explains in great detail on page 10.

The quarterly COLA formula is responsible for pay inversions.

Depending on the month of retirement, a member’s first COLA will take into account the inflation from one of the following:

- between five months and three months prior

- between four months and two months prior

- between three months and one month prior

For example, the first COLA for members who retire on June 1 is affected by inflation from the previous January but not from June. The first COLA for members who retire on July 1 is affected by inflation from June but not from July, August, or September.

These arbitrary quarterly break points contribute to pay inversions for High-3 retirees.

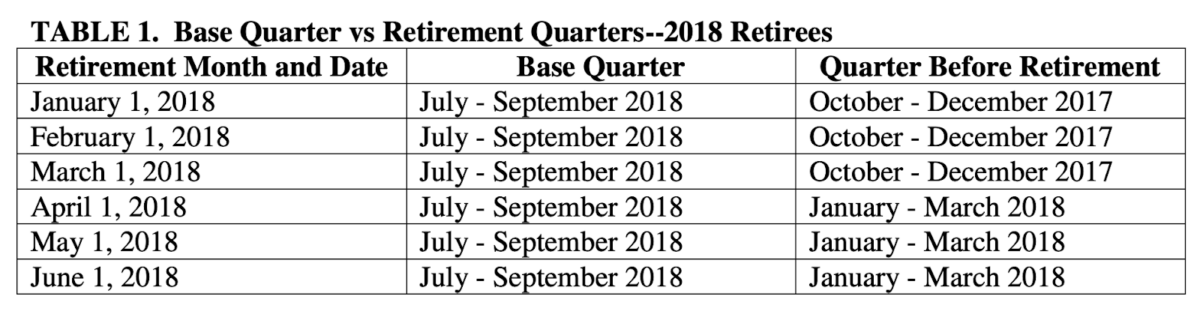

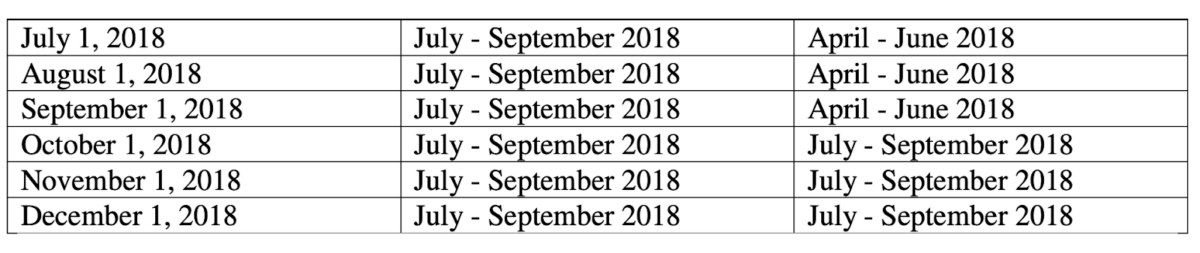

The following chart from Colonel Fowler’s thesis helps visualize retirees’ challenges.

The other cause of pay inversions under the High-3 system is that the formula does not account for inflation spikes or dips between the member’s retirement quarter and base quarter.

The COLA Trap represents a few serious problems. First, it is not fair and makes the government look incompetent.

Second, it will drive members to retire in a month that avoids the pay inversion rather than in a month that is a good fit for the member and the service. A member who otherwise might be willing to retire a month later to help the team would be hesitant if it cost them thousands of dollars over the life of their retirement.

Some experts argue that the pay inversion is insignificant because later retirees received additional months of active duty pay. Fowler cites an example using two colonels who retired in 2011, one in June and the other in July.

As Fowler notes, “The colonel who retired in July suffered a pay inversion but received $9,711 in active duty pay that the June retiree did not receive. This argument is diminished somewhat when we factor in that the June retiree received a $5,754 pension payment while the July retiree was still on active duty. In addition, if we accept as valid the argument that additional months of active duty pay outweigh pay inversions, then why has Congress consistently fought pay inversions at all? Why is a pay inversion considered bad if it happens between calendar years (which the Tower Amendment remedies), but considered acceptable if it happens within a calendar year?”

Avoiding the COLA inversion trap

Pay inversions don’t happen every year, but because members must give some notice before retiring, they should assume that an inversion will occur in their retirement year and plan accordingly.

Retire in the final month of a fiscal quarter

The best strategy for servicemembers is to retire in the final month of a fiscal quarter to avoid the pay inversion. You’ll get the same initial COLA as if you retired in the first month of the quarter but also get extra pay for longer service.

The members who retire in the first month of a fiscal quarter face the full penalty of retiring in a later quarter with a lower COLA and receiving the minimum amount of fractional years of service available within that quarter.

A later quarter is not guaranteed to have a lower COLA, but as history indicates, the quarterly COLA has never increased in a single year since the High-3 system was initiated.

There is no COLA difference between an April and a June retiree, but the June retiree will receive an extra 2/12ths of 2.5% (about 0.42%) boost to their years of service multiplier.

Do not retire in September

Another strategy to avoid pay inversion is not to retire in September, even though it is the final month of a fiscal quarter. This is because a September retiree’s COLA is based on the difference between the measure of inflation between the April/June quarter and the July/September quarter.

Because COLA increases as inflation rises, there is not enough time between the April/June quarter and the July/September quarter to make any real impact on inflation. Although September is the worst month to retire, a retirement in any month of the third quarter exacerbates the pay inversion.

Most active duty members do not know there is a separate formula for the first COLA or even such a thing as a first COLA. If they give it any thought, they logically believe that the first COLA is a prorated portion of the COLA received by those who have been retired for more than a year.

It is logical to assume that January/March retirees should receive 75% of the annual COLA because they have been retired for 75% of the year by the time the following December 1 arrives, which is when COLA percentages are determined. Carrying that forward, it’s logical to assume that April/June retirees should receive 50% and July/September retirees should receive 25% of the COLA.

That is not the case. Using historical data, third-quarter COLAs have consistently underperformed vs. other quarters. The formula is not a straightforward and linear calculation of COLA during a given year.

For example, using 2018’s 2.8% annual COLA as an example, many would expect the third quarter COLA to be at least 25% of that or 0.7%. However, it was only 0.3%, or about half of what was anticipated. By contrast, the first quarter of COLA in 2018 exceeded expectations of a first quarter COLA to be at least 75% of the annual COLA or 2.1%. It turned out to be 2.4%.

The first quarter COLAs are historically above the average, with second quarter COLAs not far behind.

Retire in March

Retiring in March is the third tactic active duty members can employ because March is the one month a year guaranteed to have no pay inversion. That’s because when a member retires in March, the quarterly COLAs for all months of the previous years have already been calculated, applied, and paid out. Instead of the pension, the March retiree earned on the day of his retirement if that March retiree could have retired on any of those previous months and earned a bigger pension plus COLA, then the retiree gets the larger amount.

A March 1 retirement date has historically provided the best initial COLA, which creates the most significant difference between two quarters of average inflation.

Also, March retirees can never have a pay inversion with the preceding January or February because all three are in the same fiscal quarter and will receive the same first COLA in December.